Listen to the story:

Hopeful Californians are looking to the Pacific this winter for an end to California’s most punishing drought on record.

The reason: what appears to be a monster El Niño in the making. The abnormally warm waters along the equator could mean a wet winter.

There are no guarantees, but there have been portents. On one Saturday in July, San Diego got more rain than it got the entire month of January.

That same month, ESPN broadcaster Dan Shulman broke the news to baseball fans from underneath a golf umbrella: “For the first time in 20 years, a game has been postponed because of rain here in Anaheim.”

You can thank Dolores for that, a hurricane that managed to make it farther north than normal. The intense Pacific hurricane season bears the fingerprints of El Niño, which is already getting hyped as a potential drought-buster.

“Yes, and deservedly so,” says Kevin Trenberth, a Distinguished Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

“For this time of year, the El Niño is as strong as it’s ever been.”

Strength in this case is measured by how much warmer surface temperatures are than normal, in the tropical Pacific. And this one looks to be about as strong as the legendary El Niño of 1997-98, which was the strongest on record, peaking at about 2.3 degrees Celsius above normal.

In the ocean, a spike of more than two degrees is like sticking a hot poker into the climate system. Pacific storms sucked up moisture from extremely warm equatorial waters and pretty much dumped it on California. San Francisco got double its normal rainfall that year.

Enter the Blob

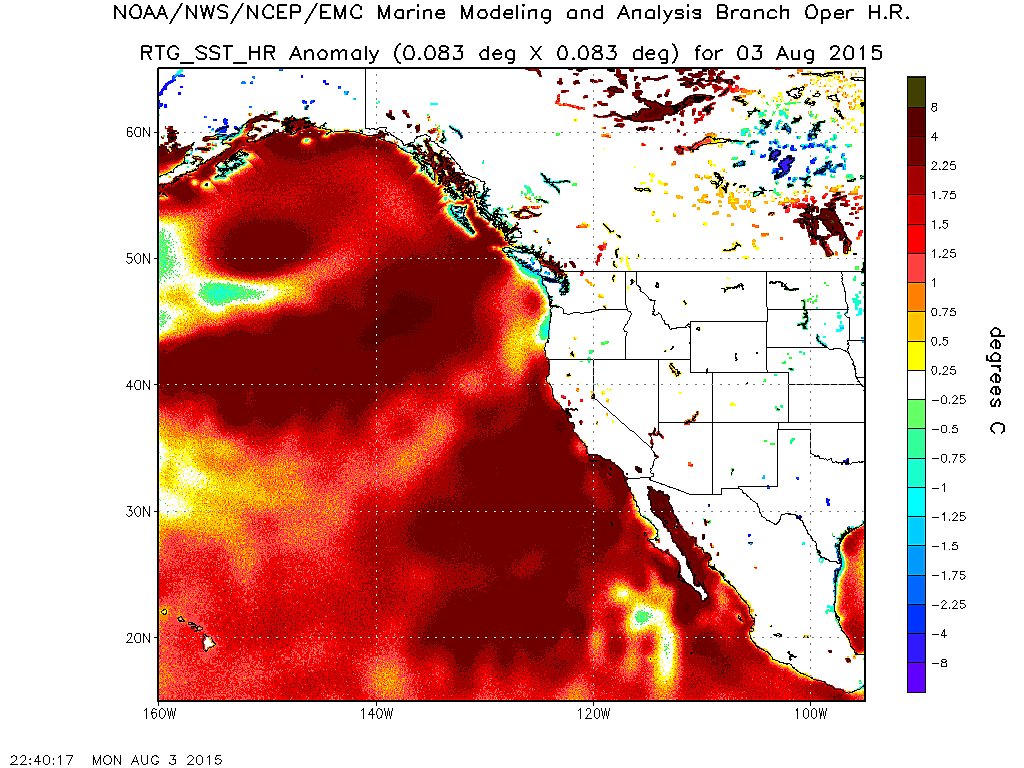

But this time around, there are other things brewing in the Pacific: patches of freakishly warm water spread far and wide, up the California coast to the persistently warm vortex, hundreds of miles across, christened by climate scientists as “the Blob.”

“That is definitely the wildcard with this El Niño,” warns Bill Patzert, a climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena and an advisor to federal El Niño forecasters.

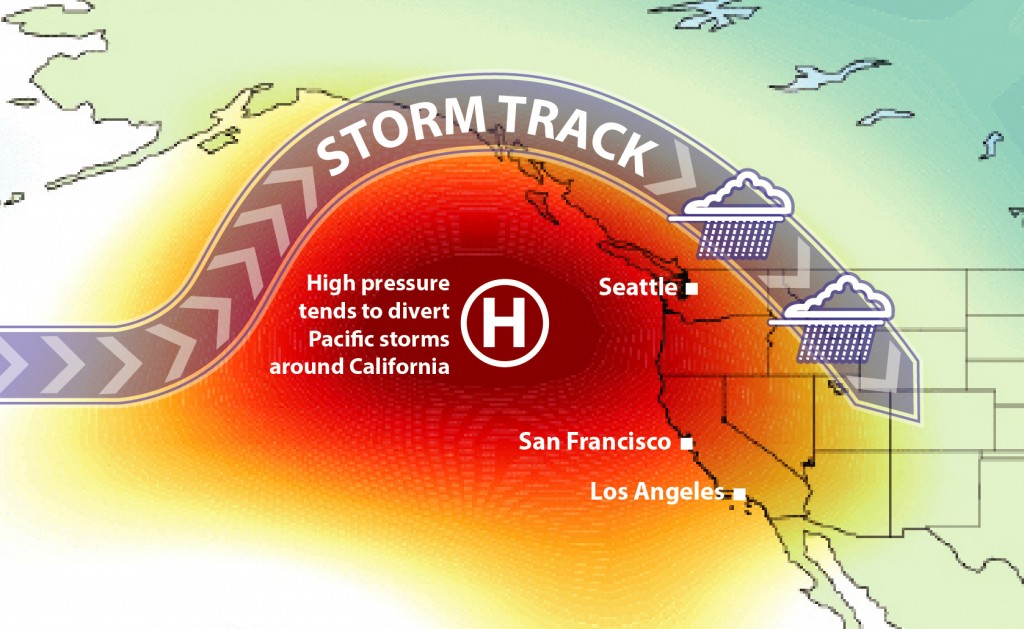

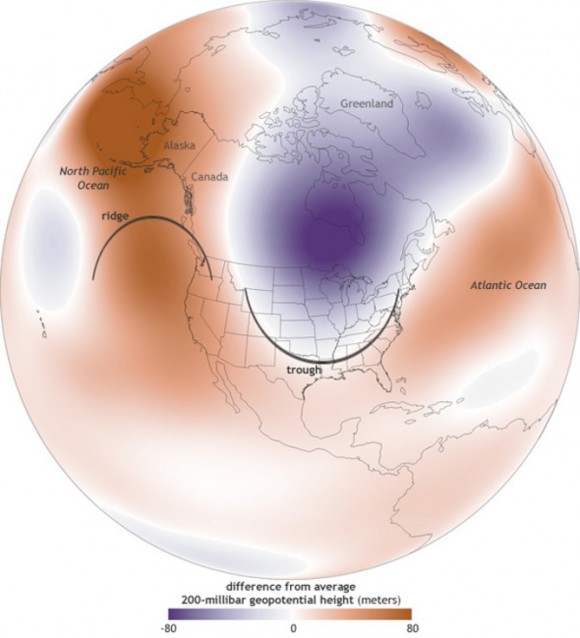

He says unlike in 1997, the Blob has been a fixture during the current drought. It’s essentially the sidekick of that “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge,” the stubborn bubble of high-pressure that’s been parked off the north coast for the past couple of years, diverting winter storms up and around California.

“And so the question is, who wins in the battle of the Blob and the El Niño,” says Patzert, “and what impact that’ll have on rainfall on the West Coast of the U.S. this fall, into the winter.”

Patzert says if the Blob and its ridge dominate, we could wring less water out of this El Niño.

“What we’re having here is battling blobs!”

But not everyone’s on the edge of their seat.

“It doesn’t fit with my concept of how things work,” says Trenberth. On the contrary, he maintains, the presence of all this warm water — especially close to the coast — could mean heavier rains from the storms we do get.

A Mixed Blessing

“The potential in California for rains to be torrential this winter is quite high because of the warm water,” Trenberth says.

That’s because, as a general rule, the warmer the water, the more moisture gets picked up by the atmosphere and by any emerging storms.

“Those storms are apt to pick up moisture from any warm water that’s lying around all along the West Coast,” says Trenberth, “and it just feeds those storms.”

That would be both good and bad news. While the reservoirs refill, the rivers could easily overfill, causing flooding and landslides — much like in 1997-98. Trenberth will take that glass as half-full.

“The way things are shaping up it sure looks like an end to the drought to me,” he says, “depending on how you define the drought.”

Patzert agrees the current El Niño is looking like a monster — “Godzilla,” to use his favorite moniker. But he’s concerned the Blob and its ridge could become at least partial spoilers, blocking out storms from the northern Pacific, leaving the door open only for El Niño-driven storms from the tropics.

That could mean Southern California gets a soaking, but the northern part of the state — where most of the major reservoirs are — misses out.

“There is almost certainly going to be a dividing line,” says Stanford climate scientist Daniel Swain. “And it’s possible that dividing line could occur somewhere in Northern California.”

Patzert hopes that isn’t the case.

“If that happens, I’m definitely going to have to go into witness protection,” he frets, “because ‘my’ El Niño, the Great Wet Hope, will only deliver half the package.”

Whatever we get, it’s a package that won’t be delivered for at least three months, when California’s long-awaited “rainy” season is due.

The extreme temperatures were evenly distributed worldwide and part of the “long-term trend,” says Gavin Schmidt of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and would have been unprecedented even without the

The extreme temperatures were evenly distributed worldwide and part of the “long-term trend,” says Gavin Schmidt of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and would have been unprecedented even without the