No one thought David Perlman would ever leave his post at the San Francisco Chronicle. Or at least, that’s what we hoped. But this week word filtered out of the newsroom that Perlman had decided that 60 years or so was enough. The Chronicle says he plans to retire in early August, “around his 99th birthday.”

KQED produced this profile of the ultra-marathon writer in 2014, when he was a mere pup of 95.

Listen:

The long view is in short supply these days and the media is often found wanting in that respect. But there’s no shortage of historical perspective from one Bay Area journalist. The San Francisco Chronicle’s science editor has been on the job for more than a half-century.

Last month, David Perlman turned 95. We’ll do the math for you. That means Perlman was born in 1918, right at the tail end of a world war — the first one. Perlman says today, young people have trouble enough envisioning the second one.

“When I say World War II, ‘When was that?’ That’s the kind of reaction I get.” He laughs ironically. “It’s sad because it just means that nobody’s teaching history properly.”

First-Hand History

Perlman got some of his own history lessons first-hand. The New York native was a copy boy at the Chronicle when reports came in of an attack on Pearl Harbor. But he admits that his early inspiration to be a journalist came from a screwball comedy: a play about fast-talking, hard-nosed newspaper reporters called The Front Page. The 1931 film adaptation was loaded with rapid-fire lines like, “Hey, listen you crazy baboon, get a pencil and paper and take this down because it’s important!” Perlman can’t quote the film but he can still quote the playwright’s description of this odd breed.

“He called them, ‘seedy, catatonic Paul Reveres, full of strange oaths and a touch of childhood.’ I wanted to be like that,” Perlman recalls. “And as a matter of fact, I got to be like that. I think I got more than a touch of childhood.”

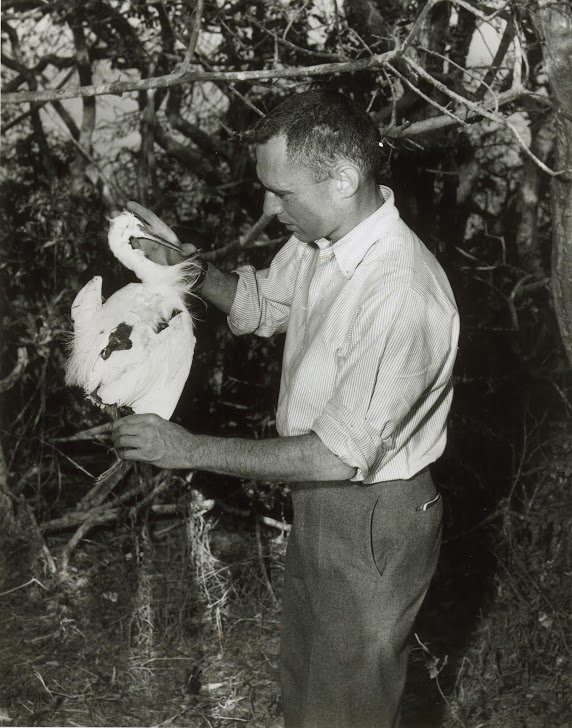

Perlman’s always retained a childlike wonder, covering the frontiers of science through five decades.

“Human evolution, let’s say — that’s a great topic,” Perlman offered, recalling the 1974 discovery of “Lucy,” the skeletal remains of a female hominid from more than three million years ago. Perlman seems to have mastered the art of evolution himself, deftly negotiating the long path from manual typewriters to Twitter. (Yes, he does on occasion, tweet from @daveperlman.)

The Final Frontier

Space is clearly one of his passions. “The universe and planets and stars and galaxies, and all the nature of the universe into which we are born.” It was space that launched Perlman’s career as a science writer, in the late 1950s. Hobbled by a skiing mishap, he found himself surprisingly engrossed in a book by British astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle, “The Nature of the Universe.”

“And I got kind of curious about what-all astronomers do — what’s all that about?” he wondered. That led him to Lick Observatory, outside San Jose, and the first of his own science writing, an article on the birth of stars.

“We didn’t have a science writer at the time, so I got to be one,” Perlman said, matter-of-factly. “And it’s been a learning experience for me ever since.”

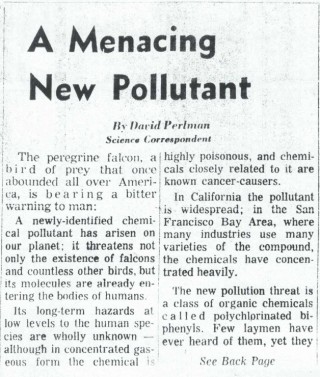

That’s a bit of an understatement. Perlman has churned out thousands of articles over the years. Not only has he won numerous science journalism awards, there are two named for him.

Perlman’s life has spanned whole epochs in science: the launch of the space age, the entire unfolding of the computer age and, as the Los Angeles Times noted in a profile, Pluto’s entire life as a planet, from its discovery in 1930, to its recent demotion to subplanet. Now he finds himself at the dawn of the “Anthropocene,” in which this planet starts to convulse from effects of the human presence.

“Everything that I see in scientific journals or talking to scientists, I have to say that climate change—global warming, whatever you call it—is real and dangerous and is going to deprive us of our sources of what we eat.”

How times have changed. He remembers the Apollo days, when it seemed like science-driven optimism had infected the whole nation.

“I do remember those days, and they were gripping. Everybody got excited about it,” he recalls. “And of course the President’s call for a space race, in a sense, and we were trying to beat the Soviets to the Moon.”

Changing Times

It disturbs him that some of that excitement has waned, as we’ve passed into a new era of scientific pragmatism. As we spoke, budget cuts threatened to close Lick Observatory, the birthplace of Perlman’s own science career.

“It is kind of absurd,” he opined. “I mean there’s a new telescope that has just been installed or developed at Lick Observatory, and it’s looking for planets far out in the Milky Way galaxy. I think it’s an extremely important telescope and why they would close the observatory just as they got a new telescope, it defeats me.”

Perlman’s been following closely the adventures of a remote-controlled rover called Curiosity, which recently found a spot on Mars where conditions once could have nurtured life.

“That’s a great discovery.” Perlman thinks it might be a step toward the ultimate discovery. “Sooner or later on that planet or elsewhere, somebody’s gonna discover some micro-organisms: microbes that are actually alive. Just think of that. That turns me on. I hope it turns other people on.”

He’d like to be around to write that story. “Oh, yeah! I’d love it.”

As he navigates the Chronicle city room from his corner cubicle (which, itself, resembles an archeological dig), Perlman has only one job complaint: it’s too quiet. Reared on the incessant clacking of typewriters and teletypes, he says the silence drives him nuts.

So Perlman returns to his cube, and fills the silence with his signature two-fingered typing. He has no plans to stop.