There’s still plenty up there for skiers but Tuesday’s manual survey of the Sierra Snowpack didn’t do much to raise hopes for an imminent end to the drought.

And time is running out.

Statewide, the Sierra snowpack stands at just 83 percent of normal levels for this date — the southern Sierra is even skimpier at 75 percent, based on estimates of the snow’s water content.

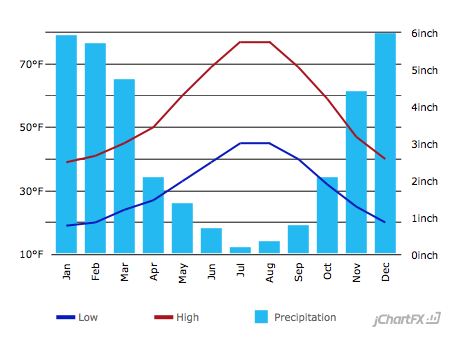

After a series of cold storms off the northern Pacific gave an encouraging start to the snow season, accumulations briefly surged ahead of long-term averages — but February’s meager rain and temperatures in record-high territory quickly started shrinking the snowpack (Locations from Sacramento to San Diego recorded their hottest February on record). That’s a major source of anxiety for the state’s water managers, who traditionally count on the so-called “frozen reservoir” for about a third of California’s water supply.

“Right now, we’re obviously better than last year,” said Frank Gehrke, who heads the state’s snow surveys, “but still way below what would be considered adequate for any reasonable level of recovery at this point.”

That’s because the rain and snow season is also shrinking rapidly. California’s precipitation tends to drop off abruptly in April, and while the rains are forecast to return later this week, rising spring temperatures will make it hard to catch up on snow.

A closely-watched indicator is the current snowpack compared to the average on April 1, when it’s generally at its peak for the season. Statewide, it’s currently just 73 percent of the April 1 average. That means the mountains need to add a quarter of one entire season’s average snow in the next four weeks, just to make it to average before the spring melt begins in earnest.

“We’re hoping for a miracle March and an awesome April,” the state’s top water regulator, Felicia Marcus told reporters last week. We might be getting a down payment over the next 10 days.

Forecasters at the National Weather Service describe the first Northern California system to arrive in March as “moisture-starved” with snowfall unlikely below 7,000 feet. But Stanford climate scientist Daniel Swain says the stronger series of storms lined up behind it could “add tremendously to the snowpack.”