February was an extremely warm month (once again) across California, with temperature records falling on a daily basis. February was also quite dry across the state, with the only precipitation event of any note occurring around the middle of the month.

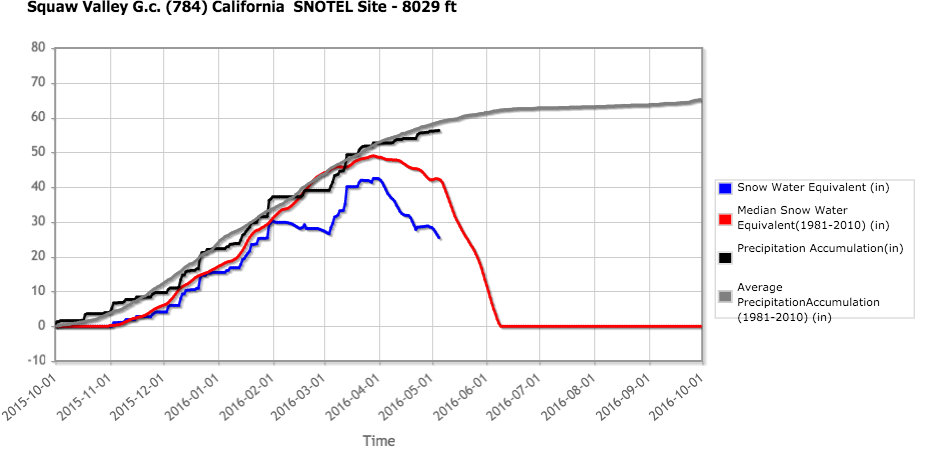

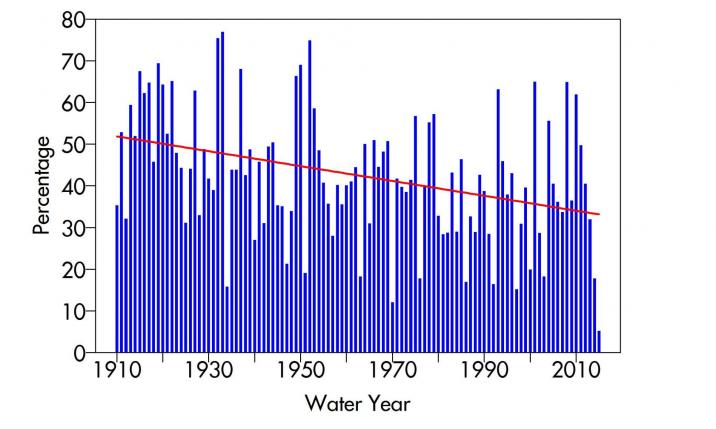

The Sierra Nevada snowpack — which had been hovering slightly above average through the end of January — started to fall behind by mid-month, and the March 1 snow survey showed statewide snowpack slightly above 80 percent of average for the date. This number is decidedly better than during recent winters, but that’s really only a testament to the abysmal snowpack accumulations during the reign of the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge (of high pressure along the coast).

Change in the Wind

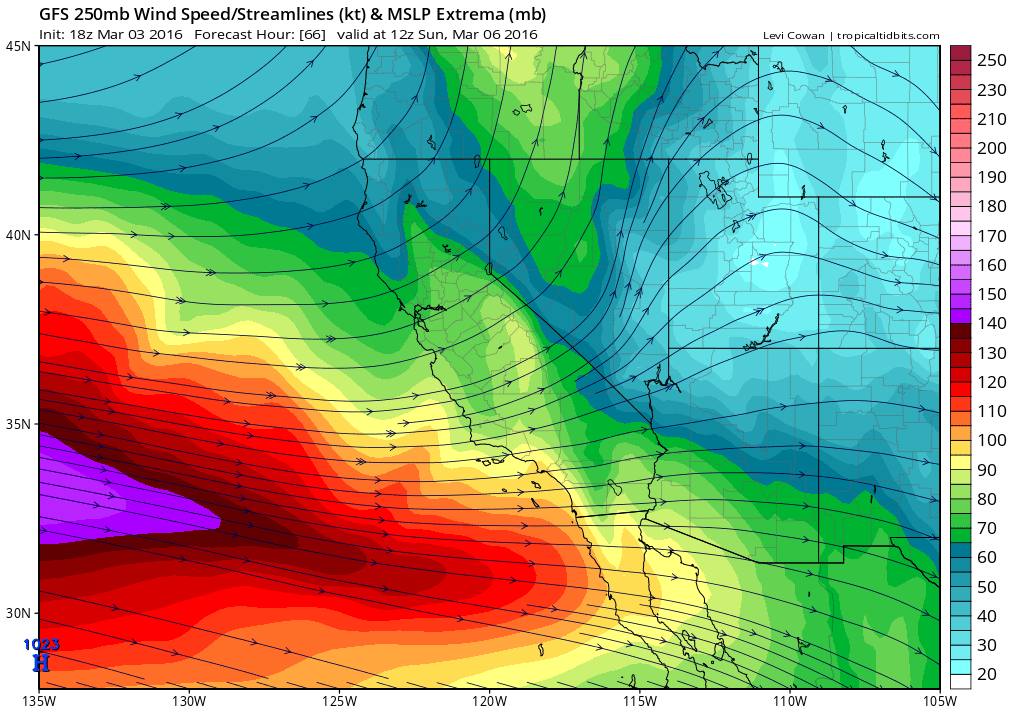

An abrupt change in the prevailing weather pattern is now at California’s doorstep, however. The persistent ridging of the past month or so is rapidly being displaced by a series of powerful storm systems, driven by a remarkable enhancement and consolidation of the Pacific jet stream.

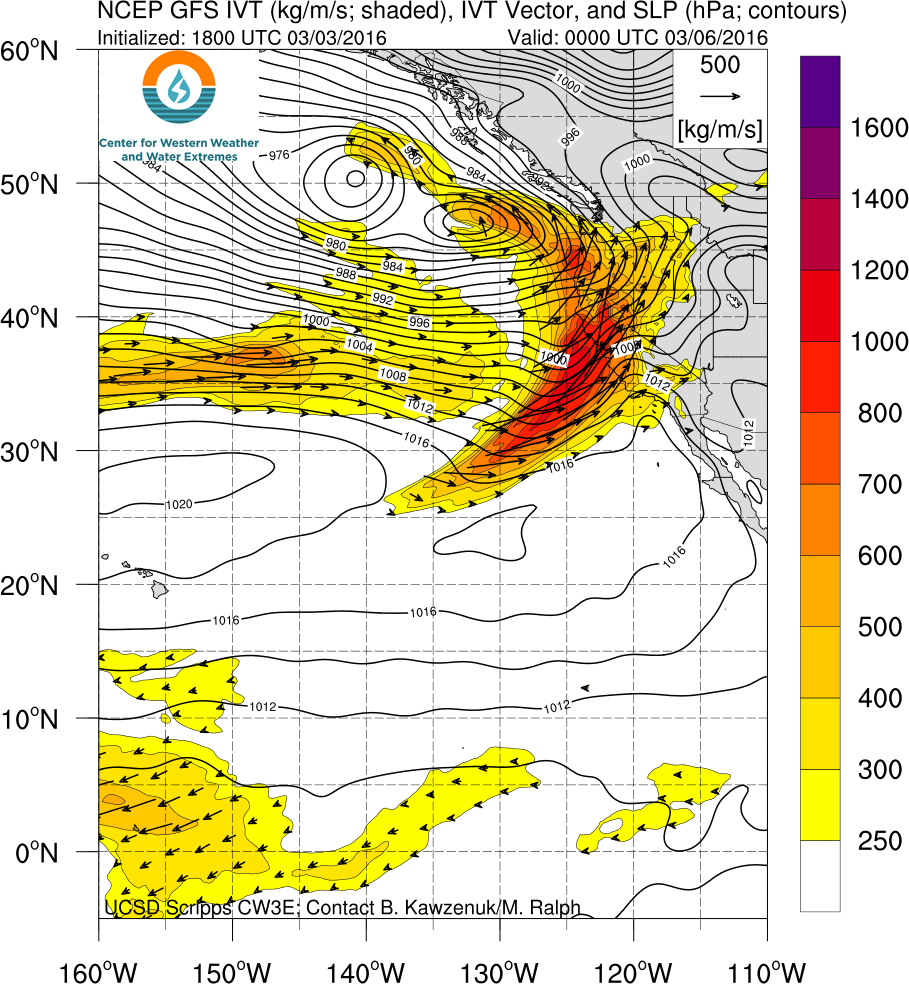

Rain has already begun across the northernmost portion of California, and will continue more or less continuously through Monday. Precipitation will gradually spread farther south on Friday and intensify on Saturday as a very strong cold front approaches the California coast. A robust atmospheric river (arguably of the Pineapple Express variety, given its subtropical origins near Hawaii) will be in place in advance of the front itself, providing plenty of moisture for the impressive larger-scale dynamics to act upon.The nose of a strong jet streak will move inland over Central California before sagging southward over time, adding lift as this storm system sweeps across the state from northwest to southeast.

Thar She Blows

The very moist atmosphere combined with a fairly impressive frontal structure will likely lead to a period of very heavy rainfall across much of California. This setup would likely be cause for significant concern if conditions had been very wet, or if the front was expected to hang up over a given location. Right now, the whole system appears to be fast-moving enough to prevent severe flood concerns — especially given our dry February. But given the high intensity of the expected precipitation, it will be worth watching closely to see if a frontal wave develops on Saturday and stalls the front more than expected. Should that occur, flood concerns would increase considerably.

In addition to impressive upper-level dynamics for this part of the world, a substantial reservoir of cold air behind the cold front will provide quite a bit of instability during and after frontal passage — leading to a decent chance of at least isolated thunderstorms across much of the state beginning later on Saturday. Strong and gusty winds — potentially 40 to 50 mph in some places — will also occur as surface pressure gradients strengthen.

A secondary system will develop rapidly late Saturday and early Sunday over the Pacific just west of California as the jet stream remains situated in an unusually favorable low-latitude position. While this surface low won’t have much time to develop before hitting the coast, it could still pack a substantial punch, particularly in Southern California. In fact, this second system could bring at least a brief burst of widespread heavy precipitation and perhaps thunderstorms to much of Southern California (focused from the Bay Area southward). There are some early indications that stronger surface-based instability could develop later Sunday or Monday across portions of Southern California, which could lead to the development of some severe thunderstorm activity near the coast.

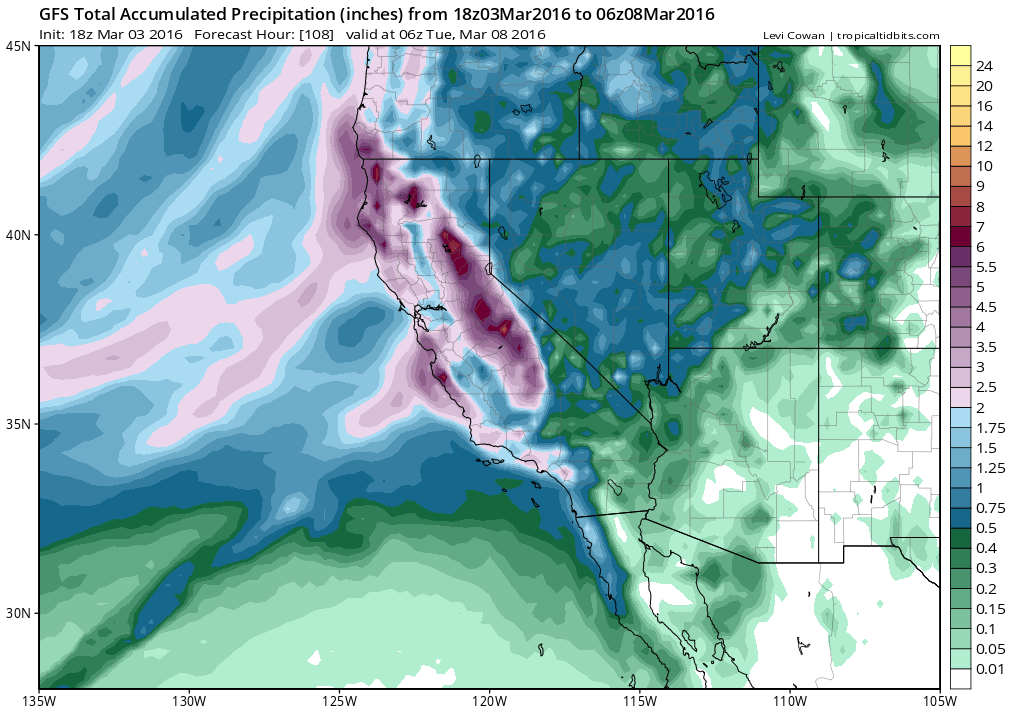

Rainfall totals through Monday across Northern California will be in the 2-4 inch range in most places (including San Francisco and Sacramento), possibly more than double that (5-8+ inches) in the coastal hills and the northern Sierra Nevada foothills. Most of Southern California will probably see rainfall more on the order of 1-2 inches, with double that in the coastal mountains. Notably, however, this precipitation will fall rather quickly, and may cause more problems that would typically be the case with precipitation of this magnitude. In the Sierra Nevada, snow levels will start out quite high as the warm atmospheric river moves ashore but will plummet later in the weekend as much colder air arrives. Several (2-4) feet of new snowfall is likely above 7000 feet, and lesser accumulations down to 4000 feet or so are likely by Monday as the secondary system moves inland.

Models Waffle

California weather (model) watchers got quite the show a couple of days ago when simulations started pointing toward an extreme precipitation event to develop next week, following this weekend’s still very heavy rainfall. The setup was one strongly reminiscent of that which makes California water wonks nervous: the occurrence of a very persistent and strong atmospheric river event focused upon a narrow stretch of the West Coast. Several model cycles were hinting at the potential for truly incredible amounts of rain and high-elevation snow between March 4 and March 12.

Fortunately, however, it now seems that those really extreme numbers are unlikely to come to pass. While a very impressive atmospheric river is still expected to develop across the eastern Pacific next week and eventually make it to California, it is not presently expected to be nearly as persistent as had been simulated a few days ago. Present models still suggest a storm that would be quite impressive by the low standards set during recent drought winters.

‘March Miracle:’ a Relative Term

In the longer run, it seems likely that a fairly active weather pattern will continue across California for much of March. It’s hard to say at this point whether precipitation this month might approach the remarkable late-season levels of the “Miracle March” in 1991, but it does at least appear likely that California’s snowpack will recover, possibly back to above-average levels in the coming weeks. It’s less clear whether Southern California will be able to make up the seasonal precipitation deficit that has accumulated this year despite the near record-strength El Niño event in the tropical Pacific. Still, it appears increasingly likely that March will at least be able to make a dent — even though it’s quite clear that California’s multi-year drought will persist through the summer.

Daniel Swain is an atmospheric scientist at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. A version of this post also appears on his California Weather blog.

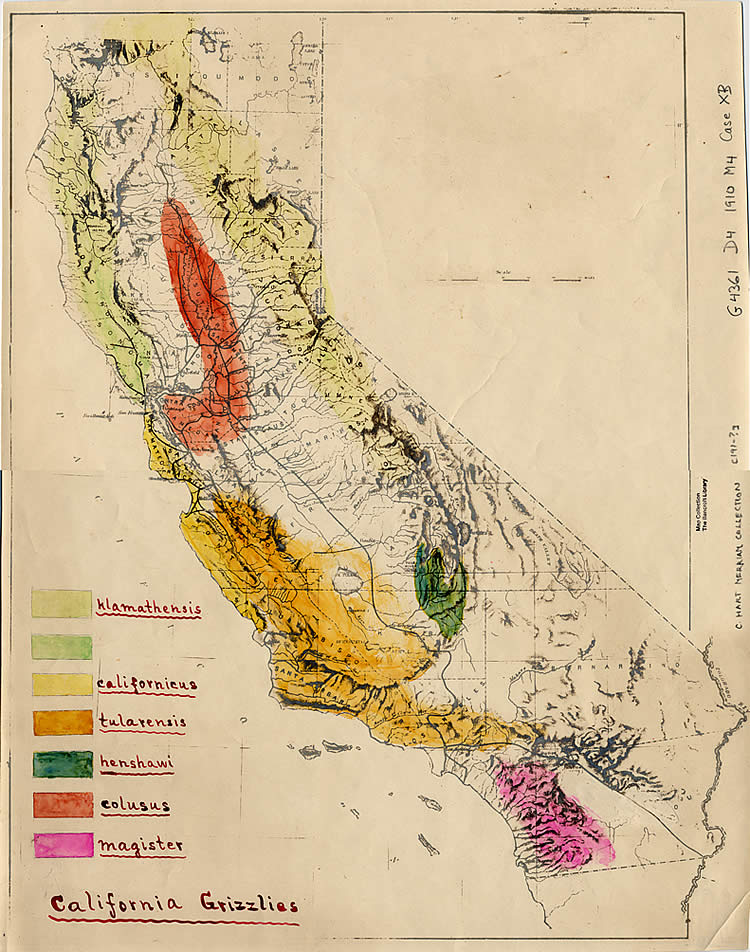

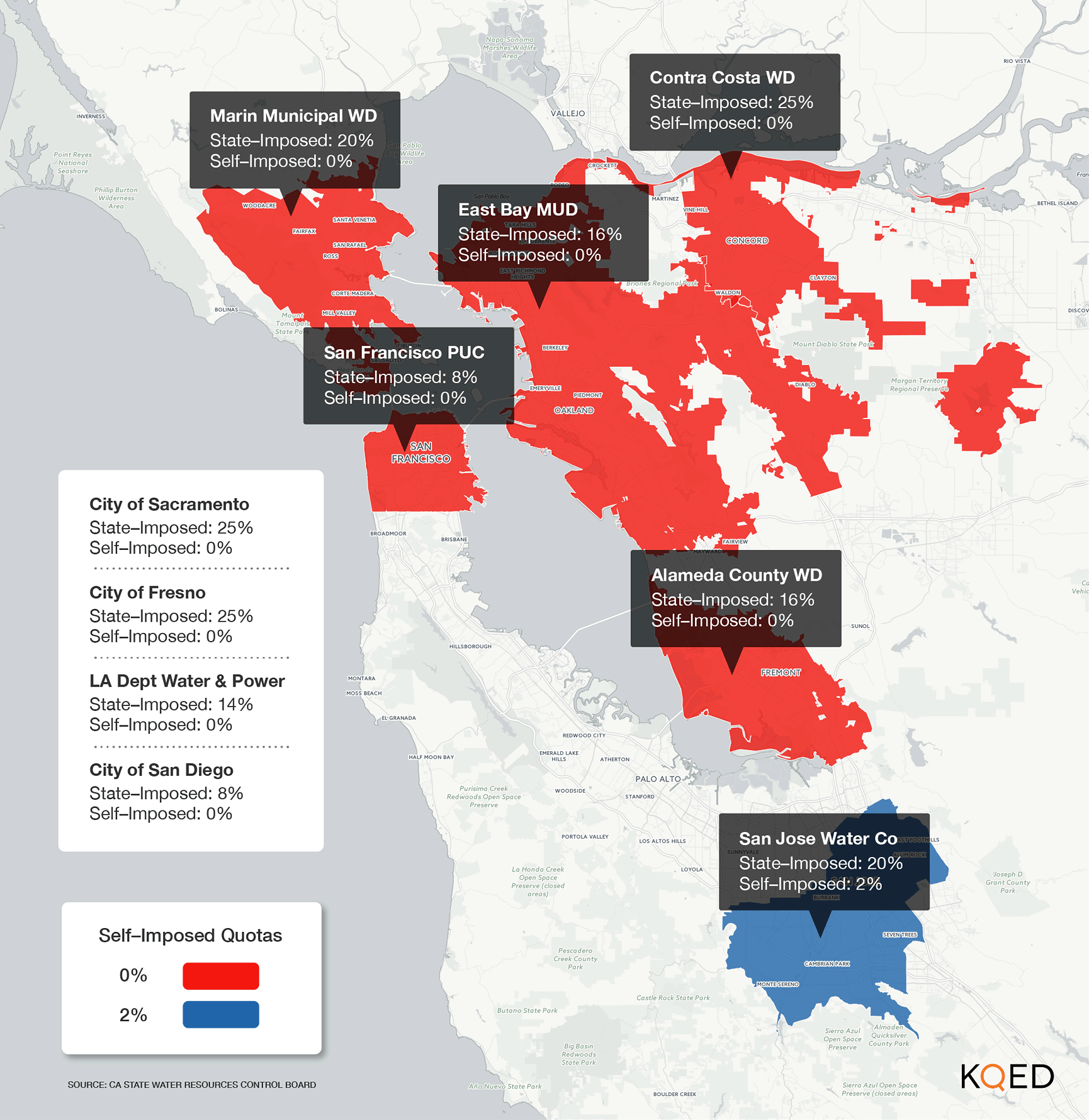

Source: Center for Biological Diversity (Teodros Hailye/KQED)

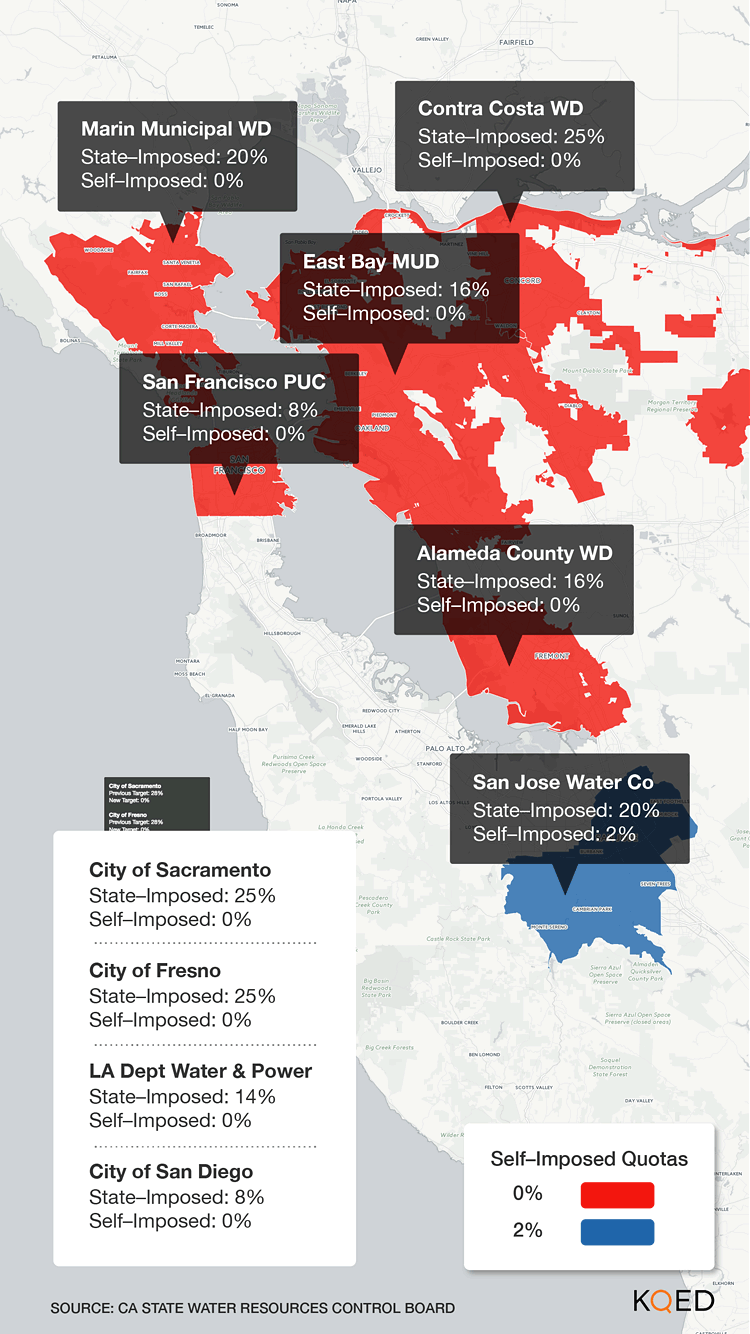

Source: Center for Biological Diversity (Teodros Hailye/KQED)